There are few things on earth – outside of politics – that are as uniting and divisive as sports. It’s probably for this reason that films about sports comprise one of the most bankable and popular genres in all of cinema. This weekend in Toronto the Canadian Sport Film Festival (taking place at the TIFF Bell Lightbox) showcases some of the best non-fiction films from around the world that celebrate, critique, and examine our cultural fascination and love of sport.

The festival, which got its start back in 2008, was founded by executive director Russell Field, an assistant professor from the University of Manitoba, a historian and year round film buff. Dr. Field’s primary research interests have always revolved around the history of sport, and more specifically how these often physical and psychological pastimes and hobbies have culturally and socially impacted people around world.

“I use a lot of film in my teaching, as many of my colleagues do, so I was always interested in sport-themed films,” Field says when asked about how his historical research blossomed into the construction of a film festival in a recent email interview. “But I also regularly attend film festivals, just as something I like to do. And I often sought out sport-themed films, of which there were many, and they regularly had significant crowds. It struck me that there was a critical mass of sport film ought there that tackled significant social issues while at the same time debunking any notion of there being a disconnect between sport as low culture and film as high culture.”

This year’s festival kicks off on Friday night at 6:30 with a screening of Keepers of the Game, filmmaker Judd Ehrlich’s look at an all female high school lacrosse team in a Mohawk First Nations community in upstate New York. It’s a perfect starting point for the 2017 CSFF because it illustrates exactly what Field says about the festival. It’s a story of teenage girls attempting to overcome rigid patriarchal and socially established traditions – ones that see lacrosse as a “gift given to men by the creator” – while also trying to navigate an underfunded public school system that finds the team barely able to hang on financially. Sure, it’s a rousing, crowd-pleasing film with vivid characters and protagonists worth rooting for, but it also touches on a great many sociological issues relevant to specific aspects of both American and indigenous societies.

“Two things are important to us at CSFF,” Field explains, “That we screen the best of the films submitted to us each year and that these films provoke dialogue about the role that sport plays in revealing important social issues. We are fortunate that in pursuing these aims, we are able to screen films and have conversations that promote a greater understanding of many different cultures.”

The selection process for this year’s ninth annual event – and the festival’s sixth year at TIFF Bell Lightbox – found the programming committee whittling down over 160 submissions of films from around the world to a total of 23 selections across ten total screenings, 22 of which are either local, Canadian, North American, or world premieres.

The festival isn’t strictly limited to its public offerings, either. Every year the CSFF has had a public outreach component with local schools. In addition to a yearly youth workshop that Field says “combines physical activity, healthy eating, discussions about film and physical activity with a hands-on filmmaking workshop,” it’s also the second year that the festival will be screening one of this year’s selections for high school students.

On Friday morning, before the local public gets a chance to see it, CSFF will take its closing night film, Crossing the Line, to Father Henry Carr Secondary School in Etobicoke, which will include a panel discussion with the subject of David Tryhorn’s documentary, former American Olympic hurdler and medalist Danny Harris.

Crossing the Line, which makes its Canadian premiere for public audiences at the festival on Sunday night at 7:45 back at Lightbox, outlines Harris’ meteoric rise through the track and field world during the sport’s biggest boom period in the 1980s, and how he was able to do it for so long while secretly battling an addiction to freebased cocaine. Harris, who broke fellow American athlete Edwin Moses’ whopping 122 race unbeaten streak in 1987 before failing to qualify for the 1988 Olympic team following a heartbreaking photo-finish loss, would find himself banned from the sport he loved, triggering a further descent into drug abuse, depression, and bizarre set of legal problems where he would be accused of a kidnapping he never committed.

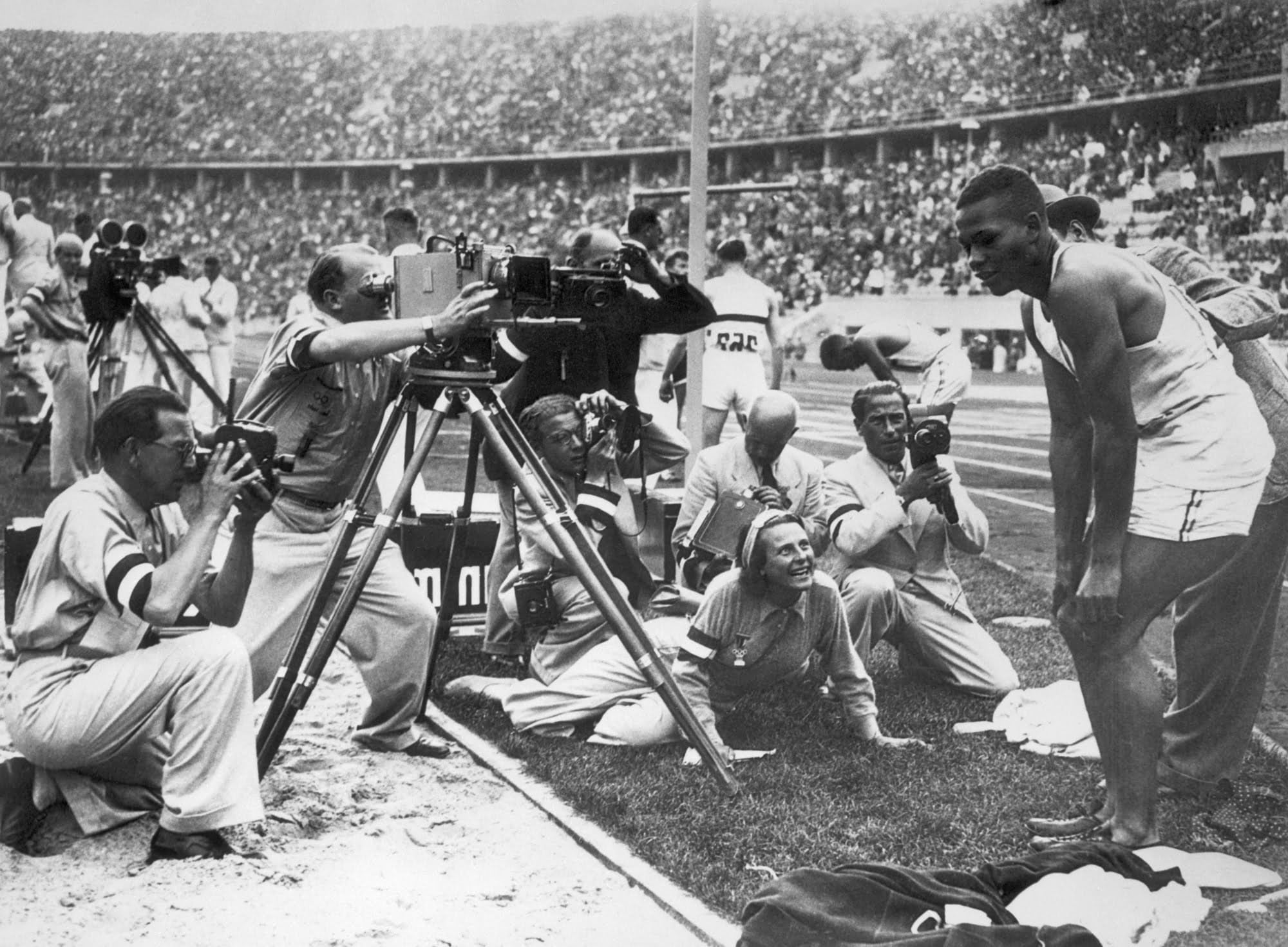

Crossing the Line is one of two films in this year’s festival that take place prominently in and around the world of Olympic athletes, the other being Deborah Riley Draper’s Olympic Pride, American Prejudice (screening Sunday afternoon at 5:00), which tells the story of the eighteen American athletes, including Jesse Owens, who travelled to Germany for the contentious and controversial 1936 games. Both films detail the struggles faced by black athletes in different eras, and both films raise critical questions about why some people remain skeptical about the world’s biggest celebration of athletic prowess.

“I like to think that all of our audience members think about the stories they see told on screen critically,” Field says about an increase in skepticism surrounding Olympic narratives in cinema. “And in a time when citizens in cities like Boston are rejecting the very notion of bidding for the Games and protests around indigenous, environmental, and economic rights converged in Vancouver, I think the idea that the Olympics need to be viewed through a critical lens is well established. Neither of [these] two films– Olympic Pride, American Prejudice and Crossing the Line – is a rah-rah celebration of the Olympics.”

Another film that looks critically at the social perceptions around sporting culture is Daniel Gordon’s incendiary, moving, and scholarly Hillsborough, which screens on Saturday evening at 6:30 and might be the biggest standout of this year’s festival selections. Gordon looks at a major logistical disaster at a 1989 soccer match in Sheffield that caused massive overcrowding that would lead to the deaths of 96 spectators. Although the primary causes of the tragedy were shoddy stadium construction and a woefully unseasoned police force that didn’t know how to control a crowd of 24,000 fans, the blame was placed for decades by the powers that be and an enabling media presence on the behaviour of Liverpool football club fans who were branded as unruly drunkards. The families of victims, survivors of the disaster, and fans alike banded together in an effort to bring the truth to light and justice to the 96 in what would become the longer inquest in English legal history.

Hillsborough illustrates that a sport film doesn’t always have to focus on the on-field action to be compelling. It could also focus on the fervent supporters who help to elevate teams, clubs, and players to mythological status, and the sometimes negative connotations that come with being fans of specific sports.

“As someone who wrote a PhD dissertation on hockey spectators at Maple Leaf Gardens and Madison Square Garden in the 1930s, I think I’m obligated to say yes,” Field quips when I ask him if the narratives of sports fans can be just as vital and compelling as those of the on field players. “For many, sport is a social experience – something to be enjoyed with others, friends and fellow fans. In many ways, it is spectators that distinguish competitive, commercial sport from physical activity and become a repository of fan affection. In turn, sport teams become important representatives of communities. A film like Hillsborough reveals the ways in which this trust and affection can be tragically and horribly misused.”

But beyond the physicality, sociology, and reverence surrounding the sporting world, this year’s CSFF also includes a film that also questions what one might define as “sport.” The Surrounding Game (screening Saturday morning at 11:30) takes a look at Go, the East Asian board game that’s often cited as the world’s oldest and most popular strategy game; one that still comes with massive amounts of player and outsider interest.

“’What is a sport?’ is a popular topic for sport philosophy classes,” Field says when asked about the inclusion of The Surrounding Game at this year’s festival. “What distinguishes sport from play or a pastime? At CSFF we define sport broadly, most often as embodied activity that can include organized sport, dance, play, and recreation. And in the past, we have screened films that dealt with all manner of these activities. Sport is a wildly popular institution; but many in their lives have felt marginalized by sport and found other outlets for their desire to be physically activity and/or to engage in competition. We want to encourage the telling of all types of stories and The Surrounding Game is an interesting story, well-told. And, while on the theme, of atypical expressions of ‘sport, The Surrounding Game is screening with the short film Harlem Knight Fight, which follows the exploits of the New York team in a modern medieval fight club.”

Regardless of the subject matter of the film’s in this year’s line-up, one thing that sport and film have in common across the past century is their ability to create indelible images that people around the world will remember as iconic moments. As long as cameras have existed, sports have given filmmakers and photographers some of pop, political, and world cultures some of their highest and lowest points. As evidenced by the film’s in this year’s festival and their subject matter, marriage between physical activity and captured images will remain some of our most vital cultural texts, but Field also hopes to show how these sometimes iconic images moments have forever been skewed by the people producing them and the cultures they’re placed into context with.

“Sport is an enterprise that is both sizeable and very public,” Field says when asked what images he personally sees as iconic throughout the recorded history. “Since the emergence of modern sport in the late-nineteenth century, sport has been a lens through which changes in society are reflected and also a contributor to change. But it has also been an institution that has embodied some of forms of exclusion and privilege. Baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson and the breaking of the ‘colour bar’ in baseball in 1947 – to the point that every team has retired his number 42 – but it is worth remembering that from the 1880s to 1946, African-Americans were systematically banned from playing major league baseball and that it took more than a decade after 1947 to integrate baseball on the field, and even longer in management positions. Selecting a ‘defining’ moment depends on one’s position. If looking for powerful images of social justice in sport, many would select the ‘black power’ salute of John Carlos and Tommie Smith on the medal podium at the 1968 Olympics. But this is a particularly North American story. Moments of protestors preventing the South African rugby team from playing matches as part of an organized anti-apartheid campaign are powerful reminders in other parts of the world. Still elsewhere, in the Global South, for example, other moments may resonate more.”

Here’s hoping that this year’s CSFF can give festival attendees a whole new set of images to think about, and new ways of looking at moments in sports history that might not have been as cut and dry as they once thought.

The Canadian Sport Film Festival runs from June 9 to June 12 at TIFF Bell Lightbox, and you can check out the festival line-up and find more information and tickets through their website.

Join our list

Subscribe to our mailing list and get weekly updates on our latest contests, interviews, and reviews.