Susanna Nicchiarelli’s eye opening and refreshingly atypical biopic Nico, 1988 looks at a music icon that died far too young without pitying its flawed subject. A look into the last two years in the life of German singer and former model Christa Päffgen – known to most in the 1960s and 70s simply as Nico – Nicchiarelli’s linear, but freewheeling drama finds tremendous depth and nuance in subtle details, and a commanding lead actress delivering one of the year’s most impressionable performances.

Trine Dyrholm stars as Päffgen, who by the time of the film’s start in 1986 hates being called Nico and would much rather talk about her recent solo material instead of past glories alongside Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground. She’s approaching 50, and the looks that once got her plenty of modelling gigs and made her a muse for Andy Warhol have long since passed. She’s living in a non-descript and borderline crappy flat in Manchester, England (which she likes because the city’s clutter and grit reminds her of post World War II Berlin where she was raised). Her long suffering managers (John Gordon Sinclair and Karina Fernandez) are setting up and coordinating what will end up being the singer-songwriter-artist’s final tours of France, Italy, and Eastern Europe, one where the notoriously difficult and demanding Nico will be working with yet another backing band. She’s still unrepentantly using heroin, albeit with a bit more control than she might have exhibited in her younger years, and she’s desperately missing the son she had to leave behind early in her career(Sandor Funtek), who’s going through his own struggles with addiction. She’s also stopped giving a shit about music or being adored by fans, and performing and recording have largely become a necessary evils.

Nico, 1988 depicts Päffgen’s final years as a series of moments and events that either confounded or comforted writer-director Nicchiarelli’s subject. There’s no story to speak of other than following along with Nico’s day to day life, and while such an approach can become distancing and obtuse in the wrong hands, Nicchiarelli (Cosmonaut) mines these moments for expert character detail that eschews hagiography and builds empathy and sympathy for a sometimes prickly, larger than life personality. A mere recitation of “the hits,” this is not, despite many dazzling and faithfully recreated musical performances.

References to Päffgen’s past aren’t hamfistedly integrated into Nicchiarelli’s overarching story. Key details about Nico’s life are mentioned frequently in polite conversation or in passing, but Nicchiarelli’s script is so tightly constructed that none of these revelations are slighted or mistreated. Every word spoken here matters greatly, and Nico, 1988 never devolves into saccharine, trite, or cautionary speeches about how those around her should have done more to help clean up a degenerating addict’s life. Nicchiarelli frames Päffgen as a perfectly functional addict; someone who displayed sometimes understandable and relatable anti-social behaviours, but was always in control of her own legacy. While Nico, 1988 doesn’t show too much of the artist’s life before this two year span, viewers unacquainted with Päffgen’s musical contributions won’t be lost or confused by such a stripped down approach. They might actually appreciate the film more as a result; getting to know Nico as a person and not as a misunderstood icon.

Stylistically, Nicchiarelli’s film is a bit more lopsided. The decision to film Nico, 1988 in minuscule full frame format is sometimes puzzling considering the vibrant nature of her subject’s life and personality. Outside of some 16mm shot flashbacks and montages, the framing choice rarely pays off, and every shot – despite being well crafted – looks like it’s about to burst at the edges. It works for intimate moments where two people are carrying on a conversation, but it also forces some of Nico, 1988’s more ambitious moments to feel claustrophobic and narrow-minded. It’s clearly an intentional decision on Nicchiarelli’s part, but it doesn’t work as well as it probably should when the film is already built around minor details that build to major themes. The shooting style employed here by Crystel Fournier has gorgeous clarity in its images, but it also becomes a reductive force on the rest of Nicchiarelli’s work.

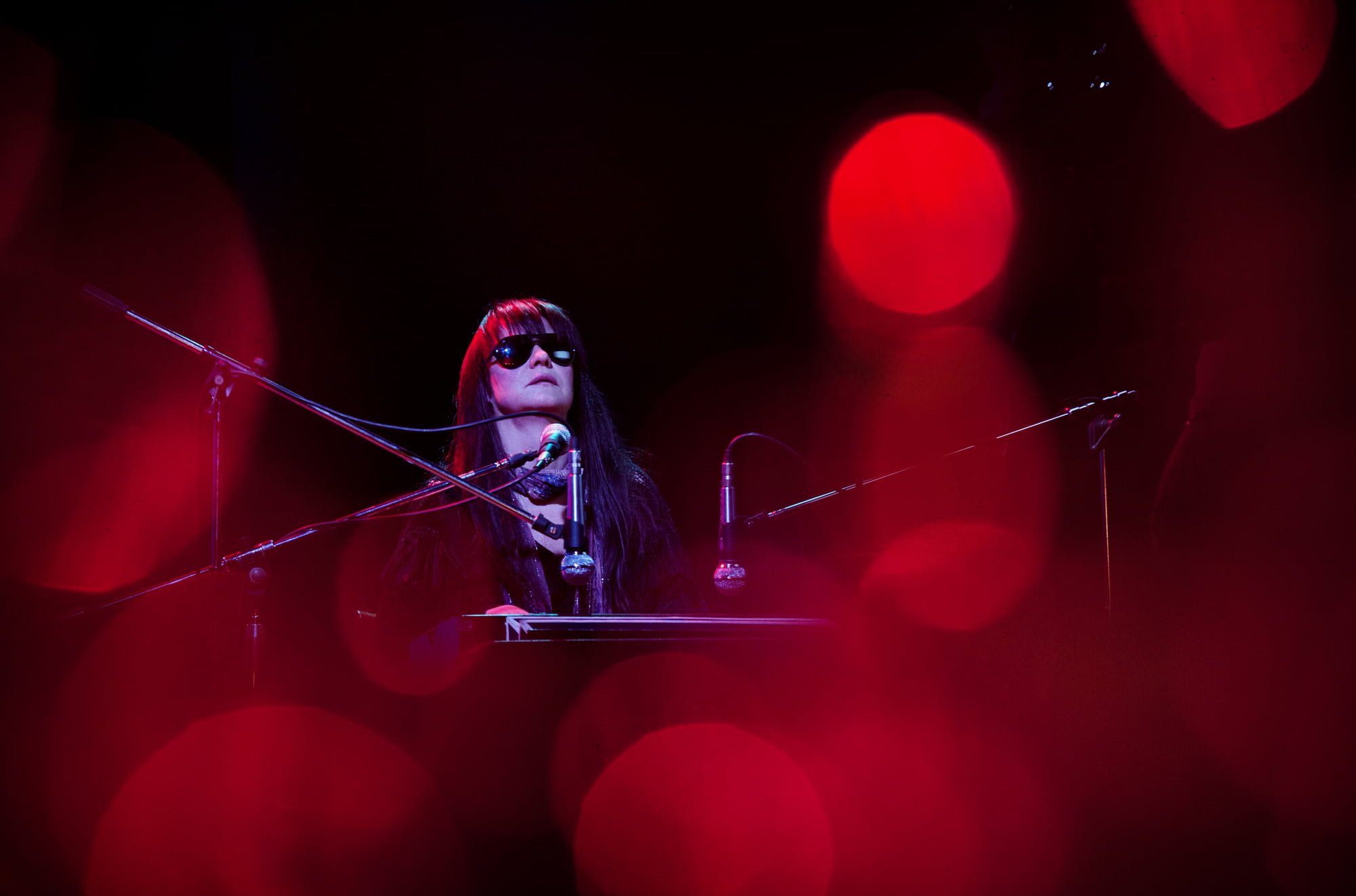

Not that Nico, 1988 has a shortage of memorable set pieces and memorable sequences. A trip to perform an illegal concert in Communist ruled Prague – one where Nico and her band are detoxing from lack of drugs – is one of the most dazzling and intense extended sojourns of any film this year. Any time Päffgen sits down with a reporter, Nicchiarelli focuses intently on Dyrholm’s face to visually show the musician’s disgust and distaste for doing press and answering the same questions over and over again. The musical performances are delivered with vibrancy and detail oriented authenticity. While the frame can’t contain everything Nicchiarelli hopes to achieve, there’s no denying the immense amount of research and dedication that has gone into Nico, 1988.

Dyrholm does her part by giving the best performance of her career and one of the best leading turns of the year. By this point, Päffgen was comfortable in her own skin; content with doing things that made her happy and vocally and visibly expressing distaste at anything the rubbed her the wrong way. Dyrholm responds in kind with a performance so lived in that it’s like watching someone lounging around in their favourite sweater, even during some of the narrative’s darkest moments. It’s difficult to make someone who has often been branded as demanding, obstinate, or solitary as a likable protagonist, but that’s precisely what Dyrholm does for Nico. Her confidence and skittishness is relatable because it’s considered. Whenever faced with an emotionally difficult situation (except, obviously, when she’s detoxing and panicked), Dryholm makes it a point to show how Nico was prone to long pauses where she considered her words carefully, in a bid to make sure she wasn’t misunderstood. It’s a remarkable performance that, in many ways, might be better to watch than a documentary about the musical icon she’s portraying. Dyrholm looks every inch like a woman who has some regrets and demons, but ultimately lived life on her own terms.

Nico, 1988 speeds up a bit too much as it heads towards some sort of conclusion, but by that point a lasting impression has been made by Nicchiarelli and Dyrholm. Nico, 1988 strips away iconography, gloss, and historical high points in favour of something far more humane and immediately relatable to anyone who watches it. Most great biopics treat famous subjects like people first and celebrities second. Few often achieve such a balance in favour of “playing the hits,” but Nico, 1988 is one of the few that keeps the recognizable and the revelatory in a near perfect balance.

Nico, 1988 opens in Toronto at TIFF Bell Lightbox, Calgary at Globe Cinema, and Vancouver at Vancity on Friday, August 17, 2018. It expands to Broadway Cinema in Saskatoon on August 24 and to Cinema du Parc in Montreal and Cinema le Clap in Quebec City on August 31.

Check out the trailer for Nico, 1988:

Join our list

Subscribe to our mailing list and get weekly updates on our latest contests, interviews, and reviews.